Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine, ongoing since 2014, has resulted in a significant displacement of people seeking safety within Ukraine. According to the Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring the Rights and Freedoms of Internally Displaced Persons”, adopted in 2014, an internally displaced person (hereinafter referred to as IDP) is a citizen of Ukraine, a foreigner or a stateless person who is legally present on the territory of Ukraine and has the right to permanent residence in Ukraine and who has been forced to leave or abandon their place of residence as a result of or in order to avoid the negative consequences of armed conflict, temporary occupation, widespread violence, human rights violations, and natural or man-made emergencies.

The transition of the war to a full-scale format in February 2022 significantly increased the number of people who have already moved and continue to move to safer regions due to active hostilities in eastern and southern Ukraine. While as of July 2021, 1,473,650 IDPs were registered in the Ministry of Social Policy, as of December 2024, according to the same Ministry, there were already 4,627,625 IDPs, 892,010 of whom were under 18.

It is already clear that a significant number of IDPs do not plan to return to their previous place of residence. Many of them have not yet decided on where they plan to reside, and others are changing their place of residence due to the movement of the front line. All these circumstances must be considered, in particular, for the effective conduct of future post-war elections. That is why the Civil Network OPORA identified key risks in the implementation of the IDPs' active and passive suffrage and proposed ways to mitigate them.

Before 2020, IDPs were not able to vote in the local elections, despite actually being members of their territorial communities. The European Court of Human Rights in its judgment in the case of Selygynenko and others against Ukraine (applications nos. 24919/16 and 28658/16) on October 21, 2021, recognized the discriminative nature of such a practice. This case dealt with the violation of IDPs’ voting rights during the 2015 local elections. The court stated, “...the applicants found themselves in a situation that was clearly different from that faced by other mobile population groups, as they were forced to leave their registered places of residence and no local elections were organised at their places of residence, as those territories were outside of the Government’s control. Therefore, despite the provisions of the IDP Act, the applicants in practice were not entitled to participate in local elections without changing their electoral addresses which were linked exclusively to their registered places of residence at the material time. The above considerations demonstrate that the applicants, as well as any other IDPs, were in a significantly different situation from citizens living at their registered places and even from other mobile groups of population who could come back to their registered places of residence and vote in local elections there. It follows that measures to put them on an equal footing with others in order to be able effectively to enjoy a right guaranteed by national law—the right to vote in local elections—were necessary in order to avoid discriminating against them.” In the end, the ECHR found that the Government of Ukraine had violated the rights guaranteed by Article 1 of Protocol No. 12 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, which provides for a general prohibition of discrimination.

The conclusions of the Civil Network OPORA's observation of the 2020 local elections stated, “The progress achieved by Ukraine in ensuring the electoral rights of citizens, especially in terms of the electoral rights of internally displaced persons..., needs to be continued at the legislative and practical levels.”

It was also mentioned that “on the eve of the 2020 local elections, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine solved the long-term problem of voting of internally displaced persons and internal working migrants in local elections. Amendments to the Law of Ukraine “On State Voter Register” allow a voter to change their electoral address by submitting an application to the State Register of Voters maintaining body. This procedure was introduced on a permanent basis, is intended to be used, as a rule, in the inter-election period, and is aimed at full political integration of citizens who are mobile within the country at their place of actual residence. In order to ensure the participation of this category of citizens in the current electoral process, the legislation provides for the possibility of submitting an application to change one’s electoral address no later than the fifth day of the official electoral process. After this deadline, voters could not apply to the State Voter Register, as the legislator takes into account the risks of destabilizing the electoral process (in particular, in terms of the formation of electoral districts) in case of a change of electoral address immediately before the election day. Thus, in the 2020 local elections, for the first time, Ukrainian citizens had the right to change their electoral address between July 1 and September 9, 2020—this possibility was used by almost 100 thousand voters. Given the short period of time for voters to apply to the State Voter Register, the number of changes of electoral addresses was not significant, but the state has every opportunity to properly inform voters about the implemented procedure.”

Positive assessments of the possibility of changing the electoral address were also expressed in the final report of the OSCE ODIHR limited election observation mission for the 2020 local elections, “...facilitated the change of electoral address, which increased the participation of citizens unable to vote at their permanent registered address, including economic migrants and internally displaced persons (IDPs)”.

Despite changes and improvements introduced in 2020, the need to engage the IDPs in the political process and decision-making at the territorial communities level remained and became particularly acute after February 2022. One of the steps to combat it was the adoption by the Verkhovna Rada of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Amendments to Certain Laws of Ukraine on Democracy at the Level of Local Self-Government” (3703-IX)” of May 9, 2024, which came into force on January 8, 2025. According to its provisions, “a resident is the citizen of Ukraine who has declared or registered a place of residence on the territory of a territorial community or whose actual place of residence/stay is confirmed by a certificate of registration of an internally displaced person (hereinafter referred to as a resident), except for a military serviceman in regular service and individuals who are in a place of imprisonment by a court order.” Thus, at the legislative level, IDPs became full members of territorial communities.

Public opinion on ensuring the electoral rights of IDPs as a vulnerable voter group in the future postwar election

From September 5 to October 7, 2024, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology conducted a study that included the questions commissioned by the Civil Network OPORA on ensuring the voting rights of vulnerable groups in the post-war elections

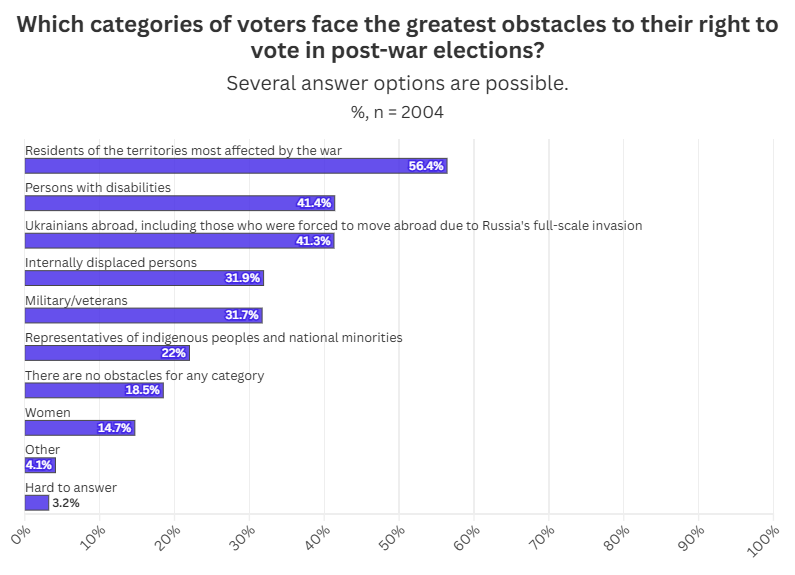

According to the data of this study, 31.9% of respondents believe that IDPs face the most obstacles to the exercise of their active suffrage.

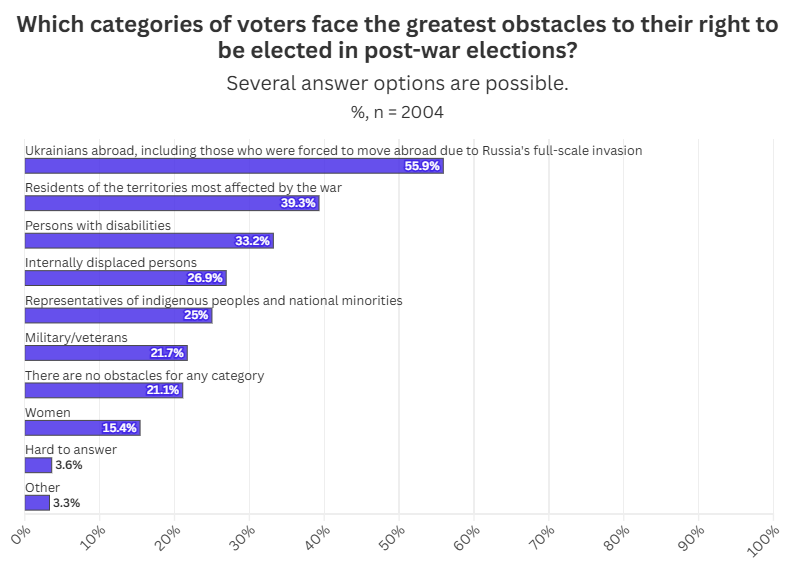

In turn, 26.9% of the respondents say that IDPs face the most obstacles to the exercise of their right to be elected.

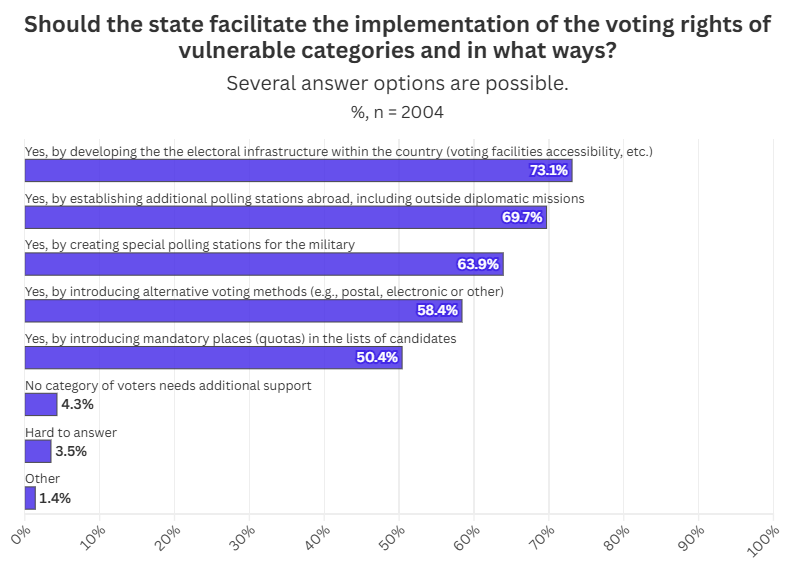

When asked about the ways to overcome obstacles to the exercise of active and passive suffrage by vulnerable groups, including IDPs, 58.4% of respondents say that suffrage should be realized through alternative voting methods (e.g., postal, electronic, or other).

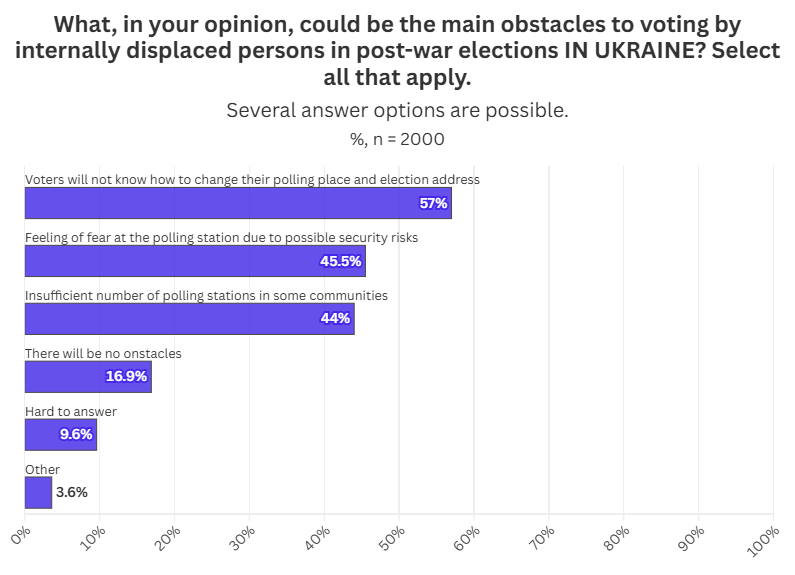

Another study, also commissioned by the Civil Network OPORA and conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology from November 18, 2024, to December 20, 2024, included a question about the main obstacles to voting for IDPs in the post-war elections. 57% of respondents believe that IDPs will not know how to change their voting place and electoral address, and 45.5% are convinced that IDPs will feel afraid at the polling station due to possible security risks. 44% of respondents say that the biggest obstacle for IDPs to vote will be the lack of polling station premises in some communities. 16.9% are convinced that there will be no obstacles for this category of voters.

Experts’ opinions on the IDPs as the vulnerable voter group

Some of the interviewed experts believe that it is inappropriate to speak of IDPs as a vulnerable group of voters since all issues related to the exercise of their active and passive voting rights have already been resolved at the level of the current electoral legislation:

“In general, there are no major problems with IDPs. There are no difficulties in the national elections and in the exercise of passive suffrage in local elections. In terms of active voting rights in local elections, the problems are hypothetically possible, but they are overcome by the norms of the current electoral legislation.”

“I see fewer problems in the national elections. This is about the temporary change of voting place and an opportunity to exercise one's right to vote. I see more problems in local elections.”

Some experts noted that “the citizens of Ukraine who have recently moved will face the most problems with the realization of active and passive suffrage in the post-war elections.”

At the same time, some experts insisted that the vulnerability of IDPs is obvious and is only getting worse:

“IDPs are a category that was vulnerable even before the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and their vulnerability had not disappeared.”

Some of the interviewed experts differentiated IDPs before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine and after 2022. According to these experts, both the state and society perceive the latter much more positively, and they receive more significant support at the legislative level:

“There are differences between the displaced people before 2022 and after. These differences are primarily at the legislative level. The state's attitude towards internally displaced persons after 2022 has also changed dramatically. They are no longer ‘separatists who are to blame,’ but the population affected by the war.”

“The IDPs who were displaced since 2014 to the present day feel the burden of stigmatization, stereotypes of “newcomers from Donetsk and Luhansk”... Internally displaced persons of 2014-2015 have experienced a lot of public rejection over 10 years, but they are more hardened, they stayed in Ukraine and rebuilt their lives. They have more experience of struggle and resistance.”

“Some of the citizens of Ukraine displaced before the full-scale invasion ask to not call them IDPs.”

Moreover, the experts pointed to the uncertainty of the IDPs’ places of residence and their wait-and-see attitude, i.e., monitoring events in the territories from which they have moved in order to return to their previous place of residence as soon as possible.

“...at the first postwar election, another relevant problem will be the uncertainty of one's place of residence. Some will want and expect to return, while others will actually decide whether to return to their abandoned place of residence or not.”

“A significant number of IDPs plan to return to their abandoned place of residence as soon as this territory is unoccupied or the fighting is over. I must note that the decision to stay in the host community is influenced by the level of integration and adaptation of IDPs, which, in particular, includes the availability of social connections, housing, work, necessary infrastructure, etc.”

Implementation of active electoral right: main challenges

According to the experts, the main risk of exercising the active voting right of IDPs will be their unwillingness to participate in voting due to various factors: personal, economic, social, psychological, etc.

“...IDPs are a vulnerable group from the point of view of financial state, psychological state, from the point of view of the loss of all belongings… and voting is the last thing they are concerned about.”

“...the support network influences one’s desire to go to the election. Talking to your friends, colleagues, and relatives about the elections makes you more willing to go to the polling station. It's very different when you are alone in a new place, none of your colleagues or friends are around, you don't really want to make new acquaintances, and therefore, the desire to go and vote in the elections decreases.”

“...if you do not encourage those people to go to the polls, they will not come...”.

Other risks include the organization of polling stations, especially in the regions that hosted the largest number of IDPs after the start of the full-scale invasion (currently Kharkiv, Dnipro, Donetsk, Kyiv regions, and the city of Kyiv).

“...a large number of internally displaced persons will not return to their abandoned place of residence. They will become voters in their new communities; therefore, electoral infrastructure and voters should be ready for this is advance.”

“...the majority of IPDs are concentrated in the eastern regions of Ukraine to be closer to their hometowns and live under social circumstances they understand. Even the very possibility of organizing voting in the respective territories will be a vulnerability.”

The next challenge will be informing IDPs about the opportunity to exercise their right to vote by participating in the elections.

“The main challenge is the low level of IDPs’ awareness and general lack of understanding of their rights, including electoral ones. Internally displaced persons are not currently focused on political rights. Most of them may not know how to vote at their new place of residence, think that they do not have the right to elect local authorities, do not know the procedure for changing their electoral address, the timeframe for such a change, etc.”

“It is important to explain that everyone's vote is important for the reconstruction of Ukraine, for the transparency of the recovery process, especially in the post-war period, and that the election results will directly affect the future of Ukraine.”

At the same time, it is important not to harm these information campaigns—not to impose on IDPs the obligation to change their electoral address, “...one must be very careful, first one have to ask the voters whether they will return. If a person is undecided, forcing them to change their electoral address is pushing them to choose to stay in the community they moved to.”

Experts consider the relevance of the data in the State Voter Register, the possibility of their prompt change and support of this process by public authorities to be other problems in implementation of the IDPs’ active electoral right

“One of the most pressing issues is the availability of data on internally displaced persons in the State Voter Register with an up-to-date electoral address, which allows them to be included in the voter lists and exercise their active voting rights.”

“It is very important that IDPs do not update their data in the SVR themselves, but that the state should assist them in some way, in particular in the context of registration procedures related to the acquisition and realization of IDP status, receiving relevant financial assistance, etc. That information about their place of residence is transferred automatically to the SVR because so many people are unlikely to be able and willing to change their data and determine their voting address on their own. We can lose quite a large number of voters who need to be met and their data updated in the SVR.”

“I do not understand why the voter register no longer accepts the applications for changing the electoral address. There are people who have already decided on their place of residence; there are those who received the eRecovery certificates; there are people who received the apartments. This is a constant process, constant changes. Why not allow them to change their electoral address? Because this process must take place exactly in the inter-election period.”

Moreover, the experts underline the provisions of Part 13 of Article 20 of the Law of Ukraine “On State Voter Register,” which stipulates that a repeated change of the electoral address is possible no earlier than one year after the date of entry of the last change of the voter’s electoral address into the State Voter Register. They call this process discriminatory: “Such norm does not fully reflect the current realities and conditions of active hostilities, which affect hundreds of communities. The inability to change the voting address places those who were forced to relocate again due to the expansion of the combat zone at a disadvantage.”

Implementation of passive electoral right

The main risk in the implementation of the passive voting right of IDPs is their reluctance, due to many factors, to participate in elections (both national and local) as candidates.

The expert believe that “IDPs have, as a rule, less resources; they are financially exhausted after displacement; they have less social capital, fewer moral and psychological resources..." to exercise their passive right to vote.

Another issues is the election deposit: "The problems of exercising the passive electoral right of IDPs include the high size of the election deposit. The financial situation of many IDPs does not allow them to pay the cash deposit, which negatively affects the possibility of exercising their electoral rights."

At the same time, other expats note that “...for active citizens, the fact of internal displacement can be a new wind, a challenge, a new impulse to integrate into the community, to influence the processes in the community. We have nice and successful cases of IDPs who campaigned and got elected.”

Recommendations

To the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine:

- To adopt changes to the Electoral Code of Ukraine and the Law of Ukraine “On State Voter Register” in terms of increasing the deadlines for changing the electoral address and place of voting.

- To adopt changes to the Law of Ukraine "On the State Voter Register", which would provide for the possibility of changing the electoral address several times during the year.

To the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine through the Ministry of Social Policy:

To develop educational and informational campaign in the form of social advertising about the importance of every Ukrainian citizen’s vote and with step-by-step algorithms on how IDPs can exercise their electoral rights.

To the Central Election Commission:

- To initiate and facilitate the development of the possibility of remote application to the State Voter Register to change the electoral address and the place of voting, ensuring the security of voter data, including through the "Diia" application, without waiting for the end of martial law.

- To resume the work of the online service “Personal Voter Cabinet”, which was terminated in 2022 due to the introduction of martial law.

To the local self-government bodies:

To adopt programs for the adaptation of IDPs into the political, cultural, social, and educational space of the territorial community and and facilitate their exercise of civic participation rights.

To the political parties:

Facilitate the participation of IDPs in elections as candidates.

Disclaimer

This study is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Civil Network OPORA and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.