Money is an essential resource for politics and voter outreach. However, if not effectively regulated, it can compromise the integrity of political processes and democracies. Effective state regulation of funding of political parties and election campaigns (commonly known as political finance) and their implementation are vital for promoting the integrity, transparency, and accountability of democratic systems of government.

During 2-3 July 2024 International IDEA, in partnership with the Central Election Commission of Moldova and other leading electoral assistance providers, will co-host the 2024 Regional Eastern Europe Conference on Money in Politics. This year’s theme - Money in Politics in the Era of Globalization and Digitalization will focus the attention of the conference participants on assessing how the modern political finance regulatory frameworks cope with increasing digitalization and globalization and what new approaches are required so that the defenses against political corruption can remain effective. The conference took place in Chisinau, Moldova on 2-3 July 2024 at the Palace of the Republic (Palatul Republicii).

Recent regional trends in the region show an exponential rise in the role of the internet and online platforms in political and election campaigns and an increase in attempts at foreign influence. This trend towards increasing digitalization and globalization poses a significant challenge to political finance regulators, political actors, and democracy watchdogs. Furthermore, the rapid use of artificial intelligence continues to complicate this already challenging situation.

The conference, the 5th in this regional series held since 2016, is hosted by the Central Election Commission of Moldova, and will bring together practitioners from the regulatory agencies, political parties, and civic watchdogs from Eastern Europe. The conference series represents a unique partnership of leading election assistance providers working in the region - the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), the Council of Europe, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the International Republican Institute (IRI) and the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD).

The representative of Civil Network OPORA, digital platforms' analyst Olha Snopok, participated in the event. We present the full-text version of her speech below.

Good morning, everyone, thank you very much for inviting me to this conference and for the opportunity to talk about the challenges we face in political finance in the era of digitalization. Our panel today is pretty general and focused on the impact of technology and digital on political finance, so I would like to talk about the biggest challenge for Ukrainian civil society in the context of the next Ukrainian elections, whenever they are held. And, as you can see from the hint on the slide, the key issue for us will be social media transparency and its openness to analysis, which are slowly disappearing, just like the word "transparency" on this slide.

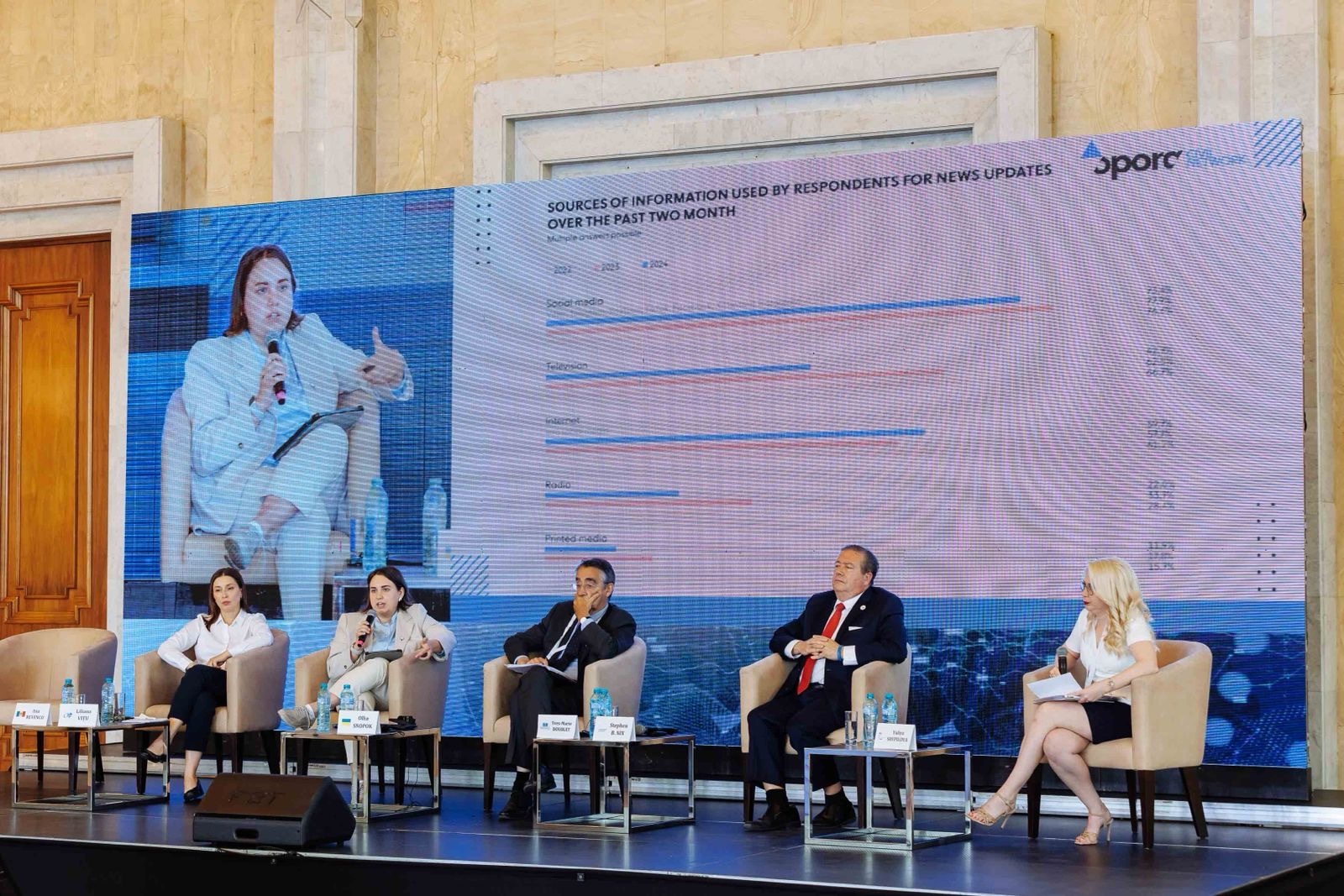

In general, for Ukraine, the digital was a pretty big issue during the previous election campaigns. In 2019-2020, for the first time, social media outstripped all other sources of information in Ukraine and became a powerful platform for campaigning among Ukrainian politicians and parties. After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian media space changed even more. Since 2022, OPORA has been conducting its annual survey of media consumption in Ukraine, and for the past three years, social media has been a key source of news for 75% of Ukrainian society. In previous years, television still had a chance to beat social media, but over the past year, trust in information on TV declined and it made social media the main source of information. So we assume that social media will become a key platform for campaigning in the next elections in Ukraine, especially since many Ukrainians are now outside the country and it will be the easiest way for parties and candidates to communicate with them.

Tracking such large and, I think, very active campaigns in the first post-war elections will be a real challenge for Ukrainian civil society and our regulatory authorities. Especially given the fact that during the last election campaigns in Ukraine, there was a tendency among politicians and parties to consider social media as some kind of a "gray" space where you can spend millions of dollars and not declare them at the end of the campaign. As you can see on the slide, during the 2019 presidential and parliamentary election campaigns, at least $2 million spent on social media campaigning was undeclared by parties and candidates in their financial reports. We managed to get these figures thanks to our monitoring of the online campaign, but at that time we had a very important advantage - the support and assistance of at least some social networks. This will not be like that during the observation campaign for the next elections in Ukraine.

In 2019-2020, the key social networks in Ukraine were Facebook and Instagram, which are owned by Meta. At that time, these social networks offered two tools for tracking campaigning: a library of political ads and a Crowdtangle service. The first allowed tracking the expenditures of politicians and parties on online political advertising, while the second allowed tracking disinformation campaigns, bots, networks of pages, etc. Thanks to the combination of these tools, OPORA identified at least 5 coordinated influence campaigns by Ukrainian politicians that could have influenced the results of the elections in Ukraine. But such things will be almost impossible during the next elections in Ukraine, because in August 2024, Meta will stop supporting Crowdtangle and now, if you want to get access to data that previously Meta just gave you, Meta wants to check all your work and each research must go through the company's review process before publication. This reduces the likelihood that the civil society and the state will be able to respond quickly to cases of disinformation influence. And this raises very serious questions about whether we will be able to effectively counter disinformation campaigns, including those from the Russian Federation, which I am convinced will be very powerful.

The example of Meta is unfortunately not a unique case. As civil society actors, we see that the general trend among social media now is reducing transparency and accessibility of data. An example is YouTube, which has been promising to think about opening a political advertising library for Ukraine for several years now, but has not done it yet. Of course, another example is social network X, formerly Twitter, where we also tried to conduct observation campaigns, but after Elon Musk came and introduced paid access to the API, we could not afford that because now full access costs about 50 thousand dollars. So, social networks today are ready to respond to requests from big players like the US or the EU, but countries like Ukraine, which are not under the umbrella of the GDPR and the Digital Services Act, cannot just talk to social networks about the needs of political finances monitoring during elections.

And for me, the most striking example here is Telegram, which is the largest source of information for Ukrainians both inside and outside Ukraine. OPORA regularly monitors this social network, and this network will likely become a key platform for political campaigning in the next Ukrainian elections, because, as you can see from the percentages, it is the most popular in Ukraine. And by coincidence, it is the most non-transparent social network.

Just a few points here: 1) First. Telegram refuses to cooperate with governments and civil society and refuses even start a conversation about changing its policies and adapting them to the electoral context; 2) Second, this company was created and is run by a Russian developer, and most likely has close ties to Russian special services; 3) Third. Russia is now very good at using Telegram to create disinformation campaigns, and this most likely means that disinformation campaigns will be huge in this social network during the next Ukrainian elections. In the context of Russia's success on Telegram, I can just give you the example of the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine, which we have been researching for the past two years. In 2022, OPORA found about 600 active propagandistic Telegram channels created by Russia in the territories occupied after the start of the full-scale invasion. Earlier this year, we conducted this research again and found almost 2000 channels like that. So when we think about the next Ukrainian elections, I suppose that we will see a similar situation in the field of campaigning, and due to the lack of monitoring tools for Telegram, we will not be able to effectively counteract here. And the situation will be pretty similar when we talk about TikTok, which is not as popular as Telegram, but it's growing its audience among Ukrainian young people. And now we see how TikTok is becoming a tool for influencing elections in different countries around the world, including the EU. This platform also does not allow monitoring of political campaigns.

To summarize, I want to say that the situation we are seeing is quite alarming. We see at the same time the growing popularity of the use of digital and technology for campaigning, the growing likelihood of external interference in the electoral process, and at the same time a decrease in transparency of all key social networks. And unfortunately, as of today, I can say that in such circumstances, civil society organizations and government agencies from countries outside the EU are unlikely to be able to ensure sustainable and effective monitoring of public finances and disinformation campaigns during elections.

On this positive note, I'm done, thank you very much for your attention.